A version of this article appeared in Wing Chun Illustrated in February 2014.

The blockbuster Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, directed by Ang Lee and starring Chow Yun-fat, Michelle Yeoh and Zhang Ziyi, remains one of the greatest and most influential foreign-language films to have been shown in the United States. Premiering in the year 2000, the movie won over 40 awards and took in US$128 million, becoming the highest-grossing foreign film in American history.

But few non-Chinese know that the movie was based on a late 1930s wuxia, or “martial hero” novel, by Wang Dulu set in the Qing Dynasty, and even fewer know what the film title really means.

Chinese use the expression “crouching tiger, hidden dragon” to describe gifted or skilled people who live and work among us, but whose extraordinary talents are shrouded by their seeming ordinariness. They are the invisible “tigers and dragons” that appear in their true form to only a few.

Here in Hong Kong, such people are everywhere and found in the most unsuspecting places. It is not uncommon to learn that the handyman in your apartment building is also a master calligrapher or the office cleaning lady teaches taichi or sings Cantonese opera.

Seventy-five-year-old Wong Long is one of these hidden dragons. Born in the year of the tiger in 1938, Wong is a third generation Hong Konger from Aberdeen, a former fishing village now famous for its floating seafood restaurants. After finishing school, Wong joined the Kowloon Motor Bus Company, where he worked as a guard and then an inspector for 15 years. He later took similar jobs in various hotels around Hong Kong until his retirement in 1997, the year the city returned to China.

But seeing the septuagenarian recently at the Fortune Restaurant in Shatin, where he goes every morning for his dim sum, you would never suspect that he was also part of an elite circle of men and women to have trained in the late 1950s and early 1960s in the Chinese martial art of Wing Chun under the late Grandmaster Yip Man.

Relatively unknown in the 1960s, Yip Man later became famous for being Bruce Lee’s kung fu teacher, and has since become the subject of five recent hit movies, two starring Hong Kong film actor Donnie Yen. The fourth in the quintet, The Grandmasters, by award-winning Hong Kong Second Wave director Wang Kar-wai, opened last year’s Berlin Film Festival and starred another Hong  Kong film icon, Tony Leung, as Grandmaster Yip Man.

Kong film icon, Tony Leung, as Grandmaster Yip Man.

According to Wong Long, less than a handful of Yip Man’s direct students are alive today, and only a few, like Wong, still teach. He says he was drawn to the fighting arts at an early age, practicing Western boxing when he was just ten. As a teenager, however, he did not like what he saw in Hong Kong’s martial arts scene. In the 1950s, the most popular forms of Chinese kung fu were Hung Chuan, Choy Lei Fut, and Tang Lang (praying mantis). “These simply did not suit me, because they require a lot of force and physical strength,” he says. All that, however, would change.

It was 1956 and Wong was only 18. He had just started working at the Kowloon Motor Bus Company when one of Yip Man’s senior students, Law Bing, also with the bus company, introduced Wong to Wing Chun. At the time, not many in Hong Kong knew what the martial art from just across the border in nearby Foshan was, with its minimalist forms, devastating straight punches, and crushing low kicks. But Wong was intrigued and visited Yip Man’s school, which at the time doubled as his apartment in Sham Shui Po, a blue-collar neighborhood of Kowloon. Wong liked what he saw, which led him on a six-year journey during which he trained five days a week with the grandmaster, becoming one of Yip Man’s longest-running students.

Wong said the arrival of Yip Man to Hong Kong in 1949 had shaken up the local martial arts scene. While Yip Man was not famous at the time, he drew frequent challenges from other martial arts schools that wanted to know what this new kung fu style was all about. Wong witnessed one such challenge from a master of another style, which convinced him that Wing Chun was the best of the Chinese martial arts.

“Wing Chun is really special, unique among Chinese kung fu styles, because of its internal power, forward and angular attacks, efficiency of movement, and its no-nonsense punches and kicks,” says Wong matter-of-factly. “Its simultaneous striking and blocking actions and use of physics and angles for attacking also make it unlike any other martial art.” Despite Wing Chun’s ferocity, Wong thinks the best practitioners are those who have mastered its soft side, those who can deflect and absorb their opponent’s force, then find an opening to go in with chain punches to the head or finger strikes to the eyes or throat.

Today, many martial artists train their entire lives without testing their skills in real combat. But things were different in the rough-and-tumble streets of 1960s Hong Kong when it was popular to stage fights in back alleys and rooftops against other kung fu practitioners. While Wong never joined the beimo, or “skill comparison” fights, he says he had to use his Wing Chun to save his life twice, both times against multiple attackers. Once in Mongkok, he fought off three men who tried to rob him. He suspected they were low-level triad members who at the time were running amok in parts of Kowloon. The other time, two thugs with a knife tried to rob him and his girlfriend. He said he easily neutralized one with a simultaneous block and straight punch, followed by a kick to the stomach. The other quickly fled.

When asked what he thought about the current mixed martial arts, or MMA craze, Wong commented that, “It’s very commercial and relies a lot on strength, so it’s good for big guys.” To Wong, a good martial art, like Wing Chun, should allow a person to take on multiple attacks. “If you’ve got one guy on the ground or in a lock, how are you going to deal with other attackers?”

While he praises Wing Chun’s effectiveness, he laments that its standards may be slipping as future generations move away from the source. “One problem is that many sifus (teachers) today simply talk too much. You’ve really got to touch hands with your students,” he says, referring to chisau, a form of hand-to-hand sensitivity sparring. Another criticism he has of the current state of Wing Chun is that many teachers are introducing non-traditional methods. “They do this because they themselves haven’t mastered the techniques, so they change them,” Wong says laughing and shaking his head.

Wong would know about forms, says his senior student Lo Chau Fat, who points out that Yip Man chose Wong from among his students in 1960 to demonstrate Wing Chun’s most advanced form, biu gee, before a large crowd at city hall.

Wong left Yip Man’s school in 1962, after the grandmaster urged him to set out on his own. He began teaching in 1964 but never officially opened a school. While he has taught many people, all based on personal introductions, he says he’s only had seven students to whom he has taught the entire Wing Chun system of three open hand forms, the wooden dummy sets, and two weapons, the long pole and butterfly knives. “The real kung fu grandmaster acts just like a normal person,” says Lo of his teacher. “The real masters train and teach for the art, not money or fame. This is why Wong Long is so special.”

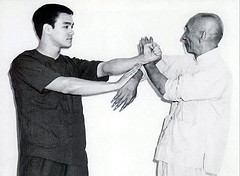

It’s a Saturday night and Wong is holding court as he does every week at a hospital recreation center in Wanchai. He is teaching a small group of dedicated students who feel lucky to be learning from one of the grandmaster’s disciples. It’s an informal gathering, with Wong’s senior student, Lo, and his students from Cheung Chau Island. At 75, with thick white hair, an actor’s chiseled chin and a weightlifter’s chest, Wong shows no signs of slowing down. He is on his feet for three hours straight coaching, demonstrating, and touching hands with all his students, often with full on punches and chops, but Wong is no worse for wear, and his students are usually the ones calling for a time-out.

While Wong teaches only once a week, he is never far from the Wing Chun world and the legacy of Yip Man. He is regularly invited out to meet with younger generation Wing Chun teachers and second-generation notables. When film director Wang Kar-wai was researching The Grandmasters, he sent his team to get advice from Wong. But Wong prefers the quiet life, getting up at 6:30am every day for his ritual of dim sum and reading the morning Chinese papers. In the summer, he goes for a daily swim at noon at one of Hong Kong’s many beaches. He spends most evenings watching television with his wife.

On the ride home after his Saturday class, the subway train lurches, sending passengers stumbling and grasping for whatever support they can find. Wong Long stands in the middle of the crowded train hardly noticing, his hands at his sides, feet firmly on the ground, his body barely budging as the train comes to an abrupt stop. One wonders how many other tigers and dragons were on the train that night.

Martin Murphy is a former US diplomat and a freelance writer living in Hong Kong (www.hongkongreporting.com). He started Wing Chun in 2004, and has been studying with Sifu Donald Mak since 2009. He took a silver medal at the 2012 1st Hong Kong International Wing Chun Cup.

Photo Gallery: Wong Long and Wing Chun in Foshan